The Indus Valley

|

| Dotted around the Indus end and its tributaries are sites of 32 towns and villages that flourished about 2500 B.C. Map shows Indus Valley in relation to the rest of India. |

William Brunton, an English architect, constructed a railroad in western India (now Pakistan) in 1856. A huge heap of dusty mounds, the remains of a long-forgotten settlement, lay along the railroad route. As a roadbed for his line, Brunton enthusiastically plundered it for bricks. Some years later, scientists visited the site and made amazing discoveries. Since the 1920s, the ruins that had been plundered have proven to be those of the ancient town of Harappa, settled 4500 years ago.

We now learn a lot about Harappan as a result of excavations. We also learn about their distant neighbors in the sister city, Mohenjo-Daro, 360 miles south of the Indus River. These towns developed double centers for more than 40 villages and cities, whose populations employed a common weight system based on a unit of 16. They also designed traditional brick buildings, fired instead of dried in the light. This suggests that wood fuel was ample for brick-kilns and that plentiful rain trees bloomed in a region in which irrigation and plants scarce today are scarce.

As in Sumer(blog 2), the cities of the Indus Valley owed their development to trade and manufacturing made possible by a surplus of grain. Bread-wheat, barley, and field peas were cultivated by farmers in the Indus Valley. They have grown cotton, woven it into a fabric and dyed it in bright colours. Like the Sumerians, they kept the animals domesticated for grain, for fur, and as burden beasts. Sheep, for instance, supplied the wool for clothes. Pigs, sheep, goats, and cattle supplied milk or beef for the farmers. Humped horses, water buffalos, elephants, donkeys, and camels were burdensome beasts.

|

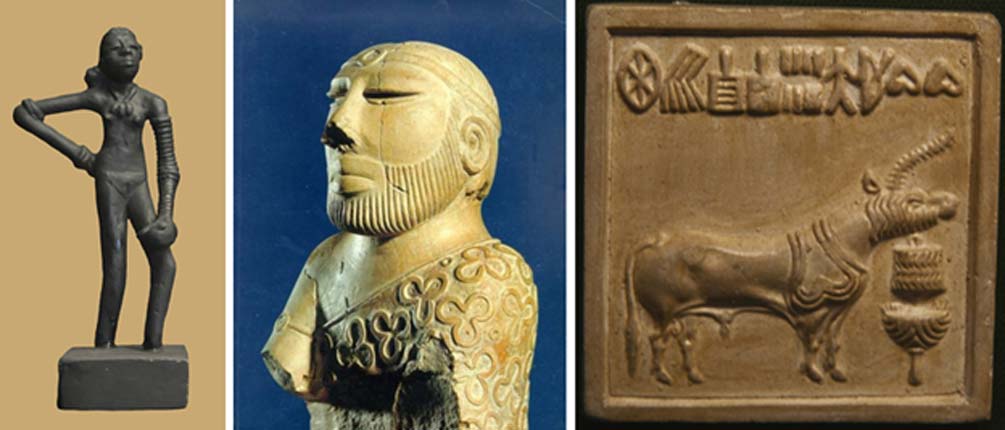

| img: Pinterest Seal imprints of bulls, tiger and elephant. |

Farmers used ox carts to bring their crops to the market, where they could exchange for city goods crafted by skilled craftsmen working metal and precious stones. From bronze and copper, artisans crafted weapons, including figures of dancing girls and canopying horses, including razors, axes, and fish-hooks. With gold, silver, lapis lazuli, amethyst, and agate, metalsmiths and jewellers crafted ritual pots, bangles, rings, and necklaces.

|

| img: ancient origin Relics give us glimpses of Indus Valley life. Above: a bronze figurine of a dancing girl, stone bust of bearded deity. |

Few of these stones and metals come from the Valley of Indus. The city dwellers had to exchange miles out for them. Boats with sails and oars were possibly plucking from the Persian Gulf around the coasts for gold. For bitumen and steatite, the donkey and camel caravans will trudge west to Baluchistan, north to Afghanistan for silver, east to Rajputana for gold. The steatite seals of Indus Valley traders have also been discovered by archaeologists in the Sumer region. Such a large trade entailed many traders and coordinated routes of trade.

|

| Town planning also seems evident in the reconstructed pattern of this city block. |

Most of the money exchanged had drifted back to Harappa or Mohenjo-Daro. Which kind of towns were they? Each stood near rivers whose seasonal flooding caused the people to lift defensive ramparts and embankments of clay. In plan both towns were close. The architects at Mohenjo-Daro, for example, built their major streets (some of them 30 feet wide) in a grid pattern separating the town into rectangular blocks. In addition, narrow lanes subdivided each street, creating a square city about a mile wide.

| The standard-size bricks seen in this excavated bath at Mohenjo-Daro suggest that powerful rulers controlled the city building. |

| In both cities, the rulers structured a drainage network much more than most other early civilizations. Rivers from the houses poured through deeper rivers, which flowed beneath the main streets and contributed to the pits getting flooded. Many houses had their own baths, and in Mohenjo-Daro, there was a big brick bath or temple tub, waterproofed with bitumen and surrounded by dressing-rooms, stood in a cloister on the citadel. |

Over several years the settlements of the Indus Valley have prospered. Instead, shortly after the year 2000 B.C., Aryan peoples* in-vaded northwest India. Such semi-barbaric invaders, mounted in horse-drawn chariots and shooting metal-tipped arrows, sacked and looted the settlements of the Indus Valley. The tragedy devastated the inhabitants of the Indus Valley. By 1200 A.D. The society had vanished.

|

| This Hittite chariot probably resembles the prehistoric battle "tanks" used by the Aryan bowmen who crushed the Valley people. |

ConversionConversion EmoticonEmoticon